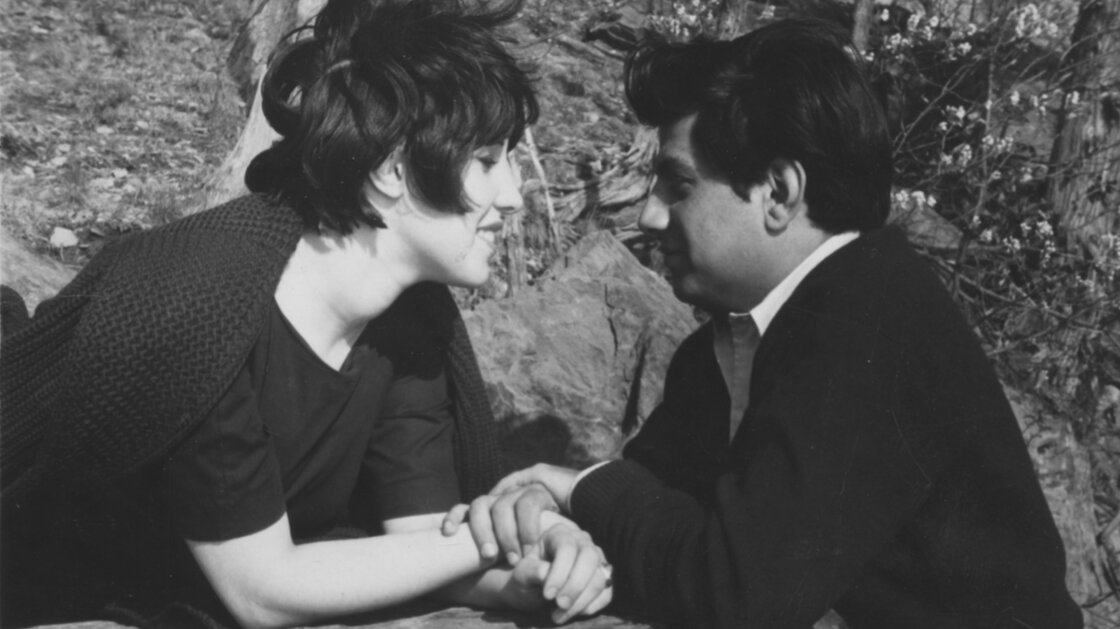

Phyllis Chesler and Abdul-Kareem

met in college. She was an 18-year-

old Jewish girl from the East Coast;

he was a young Muslim man from

a wealthy Afghan family. They

fell in love over New Wave cinema,

poetry and existentialism, and

eventually they married.

met in college. She was an 18-year-

old Jewish girl from the East Coast;

he was a young Muslim man from

a wealthy Afghan family. They

fell in love over New Wave cinema,

poetry and existentialism, and

eventually they married.

In her new memoir, An American

Bride in Kabul, Chesler tells her

story of excitedly traveling to

Afghanistan in 1961 with her new

husband, who said he wanted to be

a modernizing force in his country.

But, as she tells NPR's Rachel Martin,

her passport was almost immediately

confiscated upon arrival.

Bride in Kabul, Chesler tells her

story of excitedly traveling to

Afghanistan in 1961 with her new

husband, who said he wanted to be

a modernizing force in his country.

But, as she tells NPR's Rachel Martin,

her passport was almost immediately

confiscated upon arrival.

"I was shocked. I resisted, I refused to

give it up and I was persuaded that it's

a small matter, that it would be returned,

sent to the home. I never saw it again,"

she says. "And I tried to leave — I would

go to the American embassy and they'd

say, 'We can't help you if you don't have

an American passport.'"

Chesler soon found herself a virtual

prisoner — an Afghan wife with no rights.

prisoner — an Afghan wife with no rights.

Interview Highlights

On what her days were like in Afghanistan

My Afghan husband went off to do

something, I know not what – have tea

with minister after minister, present his

credentials and so on, which is how he

would then get his place and move up,

which he did. I was left home. I

watched my mother-in-law sew.

I watched her hit the female servants

and curse them.

something, I know not what – have tea

with minister after minister, present his

credentials and so on, which is how he

would then get his place and move up,

which he did. I was left home. I

watched my mother-in-law sew.

I watched her hit the female servants

and curse them.

On not being able to leave the house

without a male escort

without a male escort

My husband feared that if I wandered

about I would be kidnapped and raped

— an American kid in jeans and sneakers.

But progress was in the air, there was

hope in the air and my husband really

believed that Kabul would soon one

day become Paris on the Kabul River.

about I would be kidnapped and raped

— an American kid in jeans and sneakers.

But progress was in the air, there was

hope in the air and my husband really

believed that Kabul would soon one

day become Paris on the Kabul River.

On how getting horribly sick helped

her get out of Afghanistan

her get out of Afghanistan

I got dysentery, but that was not as

terrifying as the hepatitis, which had killed

every other foreigner that season. And so

I really speeded up escape plans. And at

the very last minute, when I had kind of

an escape plan in the works, my

father-in-law, a very dapper fellow,

he said, "I know about your little plan

and I think it might be better if you

leave for health reasons on an Afghan

passport, which I have procured for you."

I bless him forever for that.

terrifying as the hepatitis, which had killed

every other foreigner that season. And so

I really speeded up escape plans. And at

the very last minute, when I had kind of

an escape plan in the works, my

father-in-law, a very dapper fellow,

he said, "I know about your little plan

and I think it might be better if you

leave for health reasons on an Afghan

passport, which I have procured for you."

I bless him forever for that.

... When I got back here and I literally

kissed the ground at Idlewild [Kennedy]

Airport, I said, "Back home in the land

of liberty and libraries." I then had a

note from the State Department, by

and by, saying, "You have to leave.

You came on a visa — it's up." I said,

"Oh, sirs, I will chain myself to the

Statue of Liberty. I'm not leaving."

And it took two and a half years to

straighten it all out.

kissed the ground at Idlewild [Kennedy]

Airport, I said, "Back home in the land

of liberty and libraries." I then had a

note from the State Department, by

and by, saying, "You have to leave.

You came on a visa — it's up." I said,

"Oh, sirs, I will chain myself to the

Statue of Liberty. I'm not leaving."

And it took two and a half years to

straighten it all out.

On how she and her husband ended

things

My husband would not agree to a

divorce and I had to get an annulment.

But when he fled just before the Soviets

invaded, he came to call upon me. ...

And he said to me, he said, "I had

hoped that you would have been more

ambitious, that you would have seen

what you could accomplish in bringing

this country into the 20th or 21st centuries.

Instead, you turned tail and ran. True,

you wrote a few books for a few people,

but where does that measure up?" I was

stunned.

divorce and I had to get an annulment.

But when he fled just before the Soviets

invaded, he came to call upon me. ...

And he said to me, he said, "I had

hoped that you would have been more

ambitious, that you would have seen

what you could accomplish in bringing

this country into the 20th or 21st centuries.

Instead, you turned tail and ran. True,

you wrote a few books for a few people,

but where does that measure up?" I was

stunned.

On how she feels about him today

I sometimes think that I've yearned for

the mystical union which we represent,

for the bridging of cultures that cannot

be bridged, for the continuation of

tenderness when legal bonds have

failed. Do I forgive him? I survived

and I came away with a writer's treasure,

ultimately. And he became a muse for

this book. He's a character now in

the book and I have tenderness for

this character.

the mystical union which we represent,

for the bridging of cultures that cannot

be bridged, for the continuation of

tenderness when legal bonds have

failed. Do I forgive him? I survived

and I came away with a writer's treasure,

ultimately. And he became a muse for

this book. He's a character now in

the book and I have tenderness for

this character.

No comments:

Post a Comment