23. June 2015

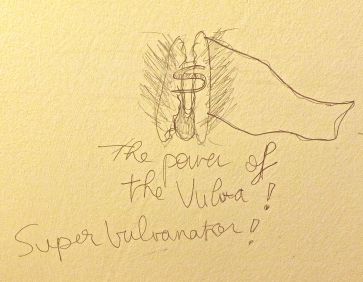

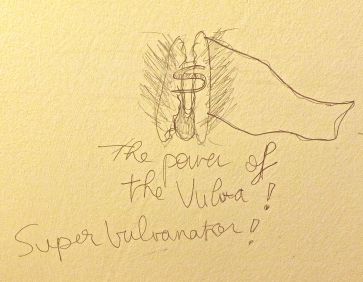

Over the course of the last six months or so, there has been a sudden proliferation of graffiti on a wall in a female toilet in one of the university libraries here in Oxford. This is, in fact, part of a longstanding tradition of notes scribbled on the walls of the library toilets, some of which survived for years before removal, and are fondly remembered by those who frequented one particular loo or another. The current crop of texts began with the question of why no one was writing on the wall, quickly followed by a call to ‘Take back the toilet wall!’ and has since expanded to include quotations of both ancient and more modern literature (in multiple languages), laments of Saturdays spent in the library (which is somewhat ironic as that’s where and when I am writing this), and general conversations about life, relationships, and graffiti. Some of my favourite scribblings ask ‘What does the graffiti really want?’, adds a bit of archaeological context by writing about a foot higher on the wall than the other texts ‘The archaeologist would conclude that most people have been writing sitting down. (This is an obvious exception)’, and finally a warning that ‘Omnia vincit cleaner.’ A few days ago I noticed a new dimension to the texts: after six months, there were finally two graffiti of a sexual nature. One commented on a desire to actually have sex in the library (with some additional commentary regarding completing such an act, and further comment on the necessity to include a second person) but the other, proclaiming the power of female genitalia, included an illustration that was both startlingly accurate and really, quite funny in concept. Behold:

Over the course of the last six months or so, there has been a sudden proliferation of graffiti on a wall in a female toilet in one of the university libraries here in Oxford. This is, in fact, part of a longstanding tradition of notes scribbled on the walls of the library toilets, some of which survived for years before removal, and are fondly remembered by those who frequented one particular loo or another. The current crop of texts began with the question of why no one was writing on the wall, quickly followed by a call to ‘Take back the toilet wall!’ and has since expanded to include quotations of both ancient and more modern literature (in multiple languages), laments of Saturdays spent in the library (which is somewhat ironic as that’s where and when I am writing this), and general conversations about life, relationships, and graffiti. Some of my favourite scribblings ask ‘What does the graffiti really want?’, adds a bit of archaeological context by writing about a foot higher on the wall than the other texts ‘The archaeologist would conclude that most people have been writing sitting down. (This is an obvious exception)’, and finally a warning that ‘Omnia vincit cleaner.’ A few days ago I noticed a new dimension to the texts: after six months, there were finally two graffiti of a sexual nature. One commented on a desire to actually have sex in the library (with some additional commentary regarding completing such an act, and further comment on the necessity to include a second person) but the other, proclaiming the power of female genitalia, included an illustration that was both startlingly accurate and really, quite funny in concept. Behold: This got me thinking: the walls of Pompeii are covered with texts of a sexual nature (some of which I’ve discussed previously here and here) both written and figural, but are these largely composed by men, or women? Of course, answering this unequivocally is impossible for Pompeii (unlike, presumably, the women’s toilet in the library), but I couldn’t help but wonder if men are more inclined to reach the point of sexual texts more quickly than women… would it have taken six months for the first penis joke to appear in a men’s toilet? To this end, I thought to look at some of the Pompeian graffiti to see if there is any discernible difference between the way men and women write or draw about sex and genitalia.

This got me thinking: the walls of Pompeii are covered with texts of a sexual nature (some of which I’ve discussed previously here and here) both written and figural, but are these largely composed by men, or women? Of course, answering this unequivocally is impossible for Pompeii (unlike, presumably, the women’s toilet in the library), but I couldn’t help but wonder if men are more inclined to reach the point of sexual texts more quickly than women… would it have taken six months for the first penis joke to appear in a men’s toilet? To this end, I thought to look at some of the Pompeian graffiti to see if there is any discernible difference between the way men and women write or draw about sex and genitalia.

Over the course of the last six months or so, there has been a sudden proliferation of graffiti on a wall in a female toilet in one of the university libraries here in Oxford. This is, in fact, part of a longstanding tradition of notes scribbled on the walls of the library toilets, some of which survived for years before removal, and are fondly remembered by those who frequented one particular loo or another. The current crop of texts began with the question of why no one was writing on the wall, quickly followed by a call to ‘Take back the toilet wall!’ and has since expanded to include quotations of both ancient and more modern literature (in multiple languages), laments of Saturdays spent in the library (which is somewhat ironic as that’s where and when I am writing this), and general conversations about life, relationships, and graffiti. Some of my favourite scribblings ask ‘What does the graffiti really want?’, adds a bit of archaeological context by writing about a foot higher on the wall than the other texts ‘The archaeologist would conclude that most people have been writing sitting down. (This is an obvious exception)’, and finally a warning that ‘Omnia vincit cleaner.’ A few days ago I noticed a new dimension to the texts: after six months, there were finally two graffiti of a sexual nature. One commented on a desire to actually have sex in the library (with some additional commentary regarding completing such an act, and further comment on the necessity to include a second person) but the other, proclaiming the power of female genitalia, included an illustration that was both startlingly accurate and really, quite funny in concept. Behold:

Over the course of the last six months or so, there has been a sudden proliferation of graffiti on a wall in a female toilet in one of the university libraries here in Oxford. This is, in fact, part of a longstanding tradition of notes scribbled on the walls of the library toilets, some of which survived for years before removal, and are fondly remembered by those who frequented one particular loo or another. The current crop of texts began with the question of why no one was writing on the wall, quickly followed by a call to ‘Take back the toilet wall!’ and has since expanded to include quotations of both ancient and more modern literature (in multiple languages), laments of Saturdays spent in the library (which is somewhat ironic as that’s where and when I am writing this), and general conversations about life, relationships, and graffiti. Some of my favourite scribblings ask ‘What does the graffiti really want?’, adds a bit of archaeological context by writing about a foot higher on the wall than the other texts ‘The archaeologist would conclude that most people have been writing sitting down. (This is an obvious exception)’, and finally a warning that ‘Omnia vincit cleaner.’ A few days ago I noticed a new dimension to the texts: after six months, there were finally two graffiti of a sexual nature. One commented on a desire to actually have sex in the library (with some additional commentary regarding completing such an act, and further comment on the necessity to include a second person) but the other, proclaiming the power of female genitalia, included an illustration that was both startlingly accurate and really, quite funny in concept. Behold: This got me thinking: the walls of Pompeii are covered with texts of a sexual nature (some of which I’ve discussed previously here and here) both written and figural, but are these largely composed by men, or women? Of course, answering this unequivocally is impossible for Pompeii (unlike, presumably, the women’s toilet in the library), but I couldn’t help but wonder if men are more inclined to reach the point of sexual texts more quickly than women… would it have taken six months for the first penis joke to appear in a men’s toilet? To this end, I thought to look at some of the Pompeian graffiti to see if there is any discernible difference between the way men and women write or draw about sex and genitalia.

This got me thinking: the walls of Pompeii are covered with texts of a sexual nature (some of which I’ve discussed previously here and here) both written and figural, but are these largely composed by men, or women? Of course, answering this unequivocally is impossible for Pompeii (unlike, presumably, the women’s toilet in the library), but I couldn’t help but wonder if men are more inclined to reach the point of sexual texts more quickly than women… would it have taken six months for the first penis joke to appear in a men’s toilet? To this end, I thought to look at some of the Pompeian graffiti to see if there is any discernible difference between the way men and women write or draw about sex and genitalia.

On face value, it would appear that the majority of graffiti of a sexual nature are written by men. Although he does not include genitalia in his catalogue of figural graffiti, Langner does discuss the appearance of scratched phallus on the walls of Pompeii and elsewhere, noting that a vagina only appears once, but in Britain, not Italy.

The graffiti themselves can be viewed with a typology: brags, insults (which may come in the form of admonishments or directions), and advertisements (for prostitutes). Leaving the last category aside, male authors (and subjects) do seem to dominate the evidence. The standard braggart type consists of proclaiming either one’s conquests or one’s abilities, whether the author’s specifically or that of the partner:

The graffiti themselves can be viewed with a typology: brags, insults (which may come in the form of admonishments or directions), and advertisements (for prostitutes). Leaving the last category aside, male authors (and subjects) do seem to dominate the evidence. The standard braggart type consists of proclaiming either one’s conquests or one’s abilities, whether the author’s specifically or that of the partner:

CIL IV 8897

Dionysios / qua hora volt / [l]icet chalare.‘Dionysios is allowed to fuck whenever he wants.’

Dionysios / qua hora volt / [l]icet chalare.‘Dionysios is allowed to fuck whenever he wants.’

CIL IV 2175

Hic ego puellas multas / futui.

‘Here I have fucked many girls.’

Hic ego puellas multas / futui.

‘Here I have fucked many girls.’

CIL IV 2145

C(aius) Valerius Venustus m(iles) c(o)h(ortis) I pr(aetoriae) / (centuria) Rufi fututulor maximum.

‘Gaius Valerius Venustus, soldier of the first praetorian cohort in Rufus’ century, the greatest of all fuckers.’

C(aius) Valerius Venustus m(iles) c(o)h(ortis) I pr(aetoriae) / (centuria) Rufi fututulor maximum.

‘Gaius Valerius Venustus, soldier of the first praetorian cohort in Rufus’ century, the greatest of all fuckers.’

CIL IV 5251

Restitutus multas decepit / sepe puellas.

‘Restitutus has often seduced many girls.’

Restitutus multas decepit / sepe puellas.

‘Restitutus has often seduced many girls.’

CIL IV 40129

Hic ego bis futui.

‘I have fucked here twice.’

Hic ego bis futui.

‘I have fucked here twice.’

CIL IV 2273

Murtis bene / felas.

‘Myrtis, you suck well.’

Murtis bene / felas.

‘Myrtis, you suck well.’

CIL IV 2421

Rufa ita vale quare bene felas.‘Rufa, may life be as good as your sucking.’

Rufa ita vale quare bene felas.‘Rufa, may life be as good as your sucking.’

Two texts, both found in the House of Fabius Rufus, written about a woman named Romula could be interpreted in a similar vein, but could just as easily be read as insulting to the woman’s character:

Fabio Rufo 34

Romula cum suo hic fellat et uubique.‘Romula sucks her man here and everywhere.’

Romula cum suo hic fellat et uubique.‘Romula sucks her man here and everywhere.’

Fabio Rufo 19

Romula viros mule trec[en]tos.

‘Romula…thousands of men.’

Romula viros mule trec[en]tos.

‘Romula…thousands of men.’

Less clear cut is the following:

CIL IV 2310b

Euplia hic / cum hominibus bellis / MM.

‘Euplia was here with thousands of good looking men.’

Euplia hic / cum hominibus bellis / MM.

‘Euplia was here with thousands of good looking men.’

Whilst at first this seems similar to the graffiti naming Romula, the qualification that the men were good looking seems to shift the identity of the writer – this is no longer simply an insult – but a statement about her ability to attract numerous handsome men. This seems less a comment on her wanton ways and more a compliment or boast on her own behalf.

One graffito describing the endurance of one woman’s activities appears to be written not by her or the man she was servicing, but by a third party, another man whose initials may indicate authorship.

CIL IV 1391

Veneria / Maximo / mentla / exmuccavt / per vindemia[m] / tota/ et relinque/t utr(umque) ventre / inane e[t] / os plenu / C(aius) S[- – – ?].

‘Veneria has sucked the cock of Maximus throughout the vintage, leaving both her holes empty and only her mouth full. Gaius S—?’

Veneria / Maximo / mentla / exmuccavt / per vindemia[m] / tota/ et relinque/t utr(umque) ventre / inane e[t] / os plenu / C(aius) S[- – – ?].

‘Veneria has sucked the cock of Maximus throughout the vintage, leaving both her holes empty and only her mouth full. Gaius S—?’

Some of graffiti offer directions, or admonishments for the abilities of one performing a sex act. Like many, the majority of these appear to be written by men.

CIL IV 4185

Sabina / felas / no belle fasces.

‘Sabina you are sucking it, but not well.’

Sabina / felas / no belle fasces.

‘Sabina you are sucking it, but not well.’

Where the sex of the author is ambiguous, it is because it can be read as either a homosexual male (even if meant as an insult to a straight male) or a female.

CIL IV 794

Lente impelle.

‘Push in slowly.’

Lente impelle.

‘Push in slowly.’

CIL IV 10041d

Piramo / cottdie / linguo.

‘I lick Pyramus every day.’

Piramo / cottdie / linguo.

‘I lick Pyramus every day.’

CIL IV 8715b

Iucu(n)dus / male cala.

‘Iucundus screws badly.’

Iucu(n)dus / male cala.

‘Iucundus screws badly.’

CIL IV 4239 = CLE 41

Fortunate animula dulcis, perfututor. / Scribit qui novit.‘Fortunatus, you sweet soul, you mega-fucker. Written by one who knows.’

Fortunate animula dulcis, perfututor. / Scribit qui novit.‘Fortunatus, you sweet soul, you mega-fucker. Written by one who knows.’

Another graffito complementing Fortunatus (though it is impossible to say if it is the same man) suggests that it could be written by a woman, as it addresses another female by name, recommending Fortunatus’ technique:

CIL IV 1230

Fortunatus futuet te inguine / veni vede, Anthusa.

‘Fortunatus will fuck you really deep. Come and see, Anthusa.’

Fortunatus futuet te inguine / veni vede, Anthusa.

‘Fortunatus will fuck you really deep. Come and see, Anthusa.’

Even those texts that refer to performing sexual acts on women are somewhat tenuous in attribution. Males sometimes insulted other men by suggesting this was in their habit.

CIL IV 4264

Iucundus cunum lingit Rusticae.

‘Iucundus licks the cunt of Rustica.’

Iucundus cunum lingit Rusticae.

‘Iucundus licks the cunt of Rustica.’

CIL IV 5178

Corus / cunnum lingit.‘Corus licks the cunt.’

Corus / cunnum lingit.‘Corus licks the cunt.’

CIL IV 1383

Isidorum aed(ilem) [o(ro) v(os) fac(iatis)] / optime cunulincet.‘Vote for Isidorus for aedile, he licks cunts the best.’

Isidorum aed(ilem) [o(ro) v(os) fac(iatis)] / optime cunulincet.‘Vote for Isidorus for aedile, he licks cunts the best.’

What strikes me about the written Pompeian evidence is that so much of it is so difficult to attribute. Although this is generally true of these kinds of texts, attempting to determine the sex of the author rather than a named individual writer seems, in theory, like it should be much simpler than it actually is. Whilst there is no doubt in my mind that some of these texts were written by women – who else but a female would write Gravido me tene(t) / Atm[etus?] (CIL IV 10231 ‘Atimetus got me pregnant.’) – it is near impossible to separate the descriptions of the acts taking place from a heterosexual interaction, an insult directed to another man, or a homosexual act. Unlike the two sexual texts I found in the female toilet of the library, the streets of Pompeii provide no agency as to who could have been there or would have scribbled such graffiti. The Roman world had very few spaces that can unequivocally be labelled as strictly single sex, and more to the point, had very different ideas than abound in the modern world not just about sexual images and commentary, but also about where and how these were expressed publicly.

No comments:

Post a Comment