Saturday, December 29, 2018

Senator Renews Calls For An Investigation Into Sweetheart Deal Given Jeffrey Epstein After Abusing Dozens Of Young Girls

Sen. Ben Sasse, R.-Neb., has demanded an investigation into the sweetheart deal given to sex offender Jeffrey Epstein who was notorious for his infamous “Lolita Express” where he took friends like Bill Clinton by plane to his private estate on the Caribbean island of Little Saint James with young girls who allegedly were used as prostitutes. Epstein was known for his preference for young women and powerful figures like Clinton were repeat guests.

Despite a strong case for prosecution, Epstein’s lawyers, including Alan Dershowitz and Ken Starr, were able to secure a ridiculous deal with prosecutors. He was accused of abusing abused more than forty minor girls (with many between the ages of 13 and 17). Sasse is correct, the handling of the case is a disgrace but it is unlikely to result in any real punishment. Certainly not for Epstein who pleaded guilty to a Florida state charge of felony solicitation of underage girls in 2008 and served a 13-month jail sentence. Moreover, to my lasting surprise, the Senate approved the man who cut that disgraceful deal, former Miami U.S. attorney Alexander Acosta, as labor secretary. The Senate did not seem to care that Acosta betrayed these victims and protected a serial abuser. In other words, everyone was protected–he powerful Johns, Epstein, the prosecutors–just not the victims who were never consulted before Epstein got his sweetheart deal.

After the deal, it was revealed that not only did Clinton take the “Lolita Express” more than previously stated but that he notably told his Secret Service details not to come on the trips to what some called “Orgy Island.” Clinton was not the only fan of Epstein. President Donald Trump referred to him as a “terrific guy” in 2002, saying that “he’s a lot of fun to be with. It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side.” Epstein is accused of abusing dozens of teenage girls and running them like a stable for powerful political and business leaders. Notably, Harvard University received a $6.5 million gift from the sex offender but decided to keep the money.

The former money manager was facing a 53-page indictment that could have resulted in life in prison in jail. However, he got the 13 month deal.

In 2007, Acosta signed a non-prosecution deal in which he agreed not to pursue federal charges against Epstein. Acosta also protected the four women who the government said procured girls for him. Various potential witnesses like Clinton and Trump would be protected from the embarrassment of trial and possibly incriminating information. Not only that but Acosta stipulated “This agreement will not be made part of any public record.” I have never seen such an effort and arrangement in the federal system. It is not uncommon to have a non-prosecution deal but the efforts made by the Justice Department to protect Epstein and these powerful men was breathtaking.

In a 2009 deposition, one key player said that federal prosecutors in Miami told him “that typically these kinds of cases with one victim would end up in a ten-year sentence.”

As for Acosta, his explanation of his handling of the case was pathetic. He wrote in 2011 that he yielded in the case because of “a year-long assault on the prosecution and the prosecutors” by “an army of legal superstars” like Dershowitz and Starr. He also wrote “The defense strategy was not limited to legal issues. Defense counsel investigated individual prosecutors and their families, looking for personal peccadilloes that may provide a basis for disqualification.” That is bizarre. Most prosecutors would have the backbone to double their efforts in the face of such pressure. Instead, Acosta’s defense came off as a whining or whimpering excuse for letting these big bad lawyers scare him off.

Conchita Sarnoff, the author of “TrafficKing,” a book on the Epstein case, also said that Acosta that “he felt incapable of going up against those eight powerful attorneys. He felt his career was at stake.” What a disgrace, but the Senate confirmed him as a cabinet member.

Notably, while victims are supposed to be consulted on such deals or decisions under the federal Crime Victims’ Rights Act, Acosta kept them in the dark and tried to conceal the whole deal until a judge years later ordered it to be unsealed.

I continue to hope for a real investigation into this case, but the same powerful figures behind Epstein are still forces in Washington. Epstein may have abused young girls by the dozens but he made sure that some of the most powerful people in the world were part of his grotesque lifestyle.

Labels:

ben sasse,

bill clinton,

jeffrey epstein,

lolita express

Bibliotheca Corviniana

Exhibition in National Gallery/Kiállitás a Nemzeti Galériában

Országos Széchényi Könyvtár

2018-19

Eredeti/Original

A Philostratos-corvina bal oldali címlapja: 1-2. Nero császár, illetve Claudius Drusus Germanicus antikizáló éremportréja; 3. Reneszánsz formai elem: aedicula ábrázolása. Az antik rómaiaknál az istenség vagy a házi istenek szobrainak elhelyezésére, vagy síremlékként szolgáltak az oszlopokkal, pillérekkel keretezett, háromszögű vagy – jelen esetben – íves timpanonnal koronázott kisméretű fülkék, illetve az azokat utánzó megoldással a falfelületek nyílásait díszítették, tagolták; 4. Mátyás magyar és cseh királyi címere; 5. A corvina ún. tartalommutatója; 6. Mátyás király antikizáló éremportréja; 7. Lorenzo de’Medici híres antik kameóját, vagyis véséssel díszített féldrágakövét festették meg. A lanton muzsikáló Apollón isten és a fuvolán játszó Marsyas szatír zenei versenyét láthatjuk. A mítosz szerint végül Apollón győzedelmeskedett, vagyis az ábrázolás a tudomány, a művészet és a szépség – így Mátyás – diadalát szimbolizálja a barbár tobzódás – a barbárság – fölött; 8. A Corvina könyvtár kifejezés rövidített alakban: COR¯ BIBLIOTHECA, vagyis Corvina Bibliotheca; 9. Reneszánsz formai elem: antik szarkofág utánzása. A domborművet idéző ábrázoláson a tengeristenek harca elevenedik meg; 10-11. Hadrianus császár, illetve az istenek közé emelt és a „tábor anyjának” nevezett Faustina császárné (Marcus Aurelius császár felesége) antikizáló éremportréja

A Philostratos-corvina jobb oldali címlapja: 12. Feltehetőleg Lucius Flavius Philostratus (Kr. u. 3. sz.) athéni szofista idealizált ábrázolása. A kódex az ő műveit tartalmazza; 13. A kutatók szerint Antonio Bonfini idealizált portréja – ő fordította le a görög szerző műveit, illetve írta a kötet előszavát; 14. A címlapokon apró Mátyás-emblémák rejtőznek, ez például egy hordó, de találunk méhkaptárt, homokórát és kutat is. A kis „szimbolikus jelecskék” pontos jelentését még nem sikerült megfejteniük a kutatóknak; 15. Az iniciáléban a Bécsújhely bevételét (1487. augusztus 17.) követő bécsi bevonulás ábrázolása ugyancsak antikizáló utalást tartalmaz: a triumphust, a győztes római hadvezérek ünnepélyes diadalmenetét idézi. A diadalkocsin egyes kutatók szerint Mátyás király áll, míg mások úgy vélekednek, hogy fiát, Corvin Jánost láthatjuk; 16. Antonio Bonfini előszavának első sorai; 17. A Mátyás-emblémák egyike: uroborosz típusú, vagyis az örökkévalóságot szimbolizáló, saját farkába harapó sárkány. Talán a Zsigmond király által alapított Sárkányrendre utalhat; 18. Valószínűleg Corvin János jegyese, Bianca Maria Sforza idealizált portréja. A milánói hercegnő és Mátyás házasságon kívül született, de törvényesített fia 1487. november 25-én kötöttek házasságot, képviselőik útján; 19. Mátyás magyar és cseh királyi, osztrák hercegi címere a morva sassal; 20. Feltehetőleg Corvin János idealizált portréjaThursday, December 20, 2018

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

Five-Year Trends Available for Median Household Income, Poverty Rates and Computer and Internet Use

For the 2013 to 2017 period, among the geographic areas with 10,000 people or more, the locations with the highest and lowest median household incomes were:

- By county and county equivalent:

- Loudoun County, Va.; Fairfax County, Va.; Howard County, Md.; Falls Church City, Va.; and Arlington County, Va., were among the highest counties by median household income.

- McCreary County, Ky.; Holmes County, Miss.; Sumter County, Ala.; Bell County, Ky.; and Harlan County, Ky., were among the lowest.

Saturday, December 8, 2018

Jason Brown’s Journey From Football to Farming

One of the highest-paid centers in the

NFL walked away from football at the

peak of his career. His new life on a

farm in Louisburg, just 30 minutes

from where he grew up, was much

harder, and happier, than he ever

thought possible.

written by LATRIA GRAHAM

PHOTOGRAPH BY ANDREW KORNYLAK

It was the off-season, but Jason Brown felt exhausted. He sat on the edge of the bed, held his head in his hands, and prayed.

God, what do you want me to do with my life?

He wasn’t prepared for the answer he got.

God, are you sure?

Jason stood up, tried to walk it off, and caught a glimpse of a face in his bathroom mirror — a face that was not quite his own. It had the same coloring, the same nose, and even the right hairline, but somehow it was a little leaner. It was Deucey, his older brother. Deucey’s real name was Lunsford Bernard Brown II, and he was dead, killed during a mortar attack in Iraq back in 2003, saving 11 other soldiers from the shrapnel that might’ve killed them, too.

Deucey was 27 years, 7 months, and 10 days old when he died. Now, it was Jason’s 27th birthday. It was 2010, and the door to play professional football was still open for him, but football wasn’t a calling. It was a job. There was an emptiness to it, one Jason tried to fill by buying a 12,000-square-foot house for his growing family and filling it with things: a television in each room and memorabilia from his career, reminders that, to outsiders, he’d made enough money to achieve the American Dream. He was, at one time, the highest-paid center in the National Football League, after signing a five-year, $37.5 million contract with the St. Louis Rams in 2009.

He’d always been good at football. He’d been a standout offensive lineman at Northern Vance High School and at UNC-Chapel Hill, where he was known as a striking space-eater in Carolina blue and white. But in 2011, Jason had a setback. The Rams took away his job as a starter. After the season, the team released him. But before all of that, Jason already knew he wanted to get back home, to the land he was raised on. He needed to remember the things he’d loved before he started playing this game for money.

For most of his life, Jason Brown and his family believed in the three pillars of the American South: Faith, Family, and Football.

After 2012, the last F changed.

Jason Brown works a muscadine vine in a beat-up straw hat.

He’s too busy to patch the holes in it, he says.PHOTOGRAPH BY ANDREW KORNYLAK

Jason is having muscadines for breakfast, fresh off the vine. He bends his 6-foot-3, 320-pound body into unimaginable shapes, combing through the vines with incredible speed for his size, a remnant of his former life. He plops the good grapes into a bowl and eats them as he explains how all of this came to be.

Jason, his wife, Tay, and their six kids live in Louisburg on a 1,000-acre parcel of pasture and farmland. It’s 30 minutes from Henderson, where Jason grew up, and where his parents still live. The property’s been a farm for more than 100 years, and the big white barn where cows were once milked stands silhouetted like an angel against a Carolina blue sky.

By the time Jason bought the land in October 2012, less than a year after leaving the NFL, his mission was already clear. “Before we started looking for farms, we made a covenant,” Jason says. “We said, ‘God, whatever land you bless us with, we’re going to name it First Fruits Farm, and we’re going to give to our neighbors. We’re going to give to our community the first fruits of everything — whatever is produced.’ ”

It hurts him to think that somebody might be hungry right down the road or across the county line, so he gets on his baby blue Ford tractor to take care of the weeds, inspired to make the most of the day before the sun goes down. He’s seen the way hunger can shape a home. He’s read about the 200,000 children in North Carolina who are never sure where their next meal is coming from. He’s witnessed the telltale signs in the eyes of kids in his hometown. He wanted to feel a little less helpless. So he was compelled to become a farmer, and to give away part of his crop to help.

First Fruits Farm in Louisburg covers 1,000 acres. The Browns have been growing crops on this land,

formerly a dairy farm, since buying it in 2012.PHOTOGRAPH BY ANDREW KORNYLAK

Jason’s working harder than he ever has, but he goes to bed with a peace of mind he’s never had before. Nobody owns him anymore, he says. Many fans who bought tickets to see him play treated him like they’d paid for a piece of his soul, expecting unfettered access to his personal life. In fact, everything about his past life, as he sees it, was virtual — all the screens, phones, tablets, televisions, social media, and video games. On his farm in Louisburg, he’s away from it all, no longer part of a sports team, spending his days in quiet atonement for his time in the spotlight. Jason doesn’t watch football much anymore. There’s one TV in the entire farmhouse. It stays off for weeks at a time.

“A few of my previous teammates have come out here,” Jason says, “but this is such a drastic lifestyle change, and some of them, they still can’t believe it. They can’t believe it’s real.”

This is his fifth year on the farm, and a lot of people didn’t think he’d last this long. They thought he’d get tired of the novelty and worn down by the monotony. But the private life of a farmer and the private life of a football player are not that different. Both require extreme discipline and the ability to think on your feet.

Still, most people have a hard time understanding how Jason could leave football behind to embrace a way of life he knew nothing about. Even now, people ask him: Why did you do it?

“Look, if you really want to know about Jason Brown, and why I left the NFL and why I came here to farm …” he trails off, slightly frustrated. He looks out into the pasture, but in his mind he’s somewhere else. “It’s Jesus, OK? There ain’t no other reason. Without Jesus in my life, I’m a horrible person. I’m a selfish person.”

Jason looks down into his bowl, half full of muscadines, unsure of what to say next.

After breakfast, Jason eases his bulk into his black pickup truck and begins to trace the perimeter of his farm, heading toward the Tar River. His eyes constantly scan the land for changes, stopping short when he sees something different.

Related Articles

Hope for Hops

Hope for Hops The Book Club at Duck's Cottage

The Book Club at Duck's Cottage Free-Range Life at Hardscrabble Hollow Farm

Free-Range Life at Hardscrabble Hollow FarmHe squints hard.

“It isn’t supposed to be doing that yet,” he says under his breath. A skinny sapling, no bigger than a stick, has a cluster of mature pecans on it, bearing fruit almost two years before it should.

Jason’s time on the farm has been like that — a series of little miracles, way ahead of schedule. In year one, First Fruits Farm grew five acres of sweet potatoes, their lush green vines snaking along the fence, heart-shaped leaves hiding the orange-fleshed gems underneath. Now he’s up to 15 acres. If all goes according to plan, this year’s harvest will reap 300,000 pounds of sweet potatoes.

Some days he wonders what Deucey would think of all this. He sometimes imagines what it’d be like if his brother were here with him, working by his side.

Out in the field Jason bends like he’s going to snap a football, but instead brings up a cluster of the sweet potatoes, turning them over in his hands, soil the color of brown sugar falling onto his boots.

This year, Brown hopes to harvest 300,000 pounds of sweet potatoes for food pantries.

He’ll save some for himself, too. “Sweet as candy,” he says of the taste.PHOTOGRAPH BY ANDREW KORNYLAK

This is just a preview, he explains. The rest of the sweet potatoes will be harvested a little later with the help of volunteers from the Society of St. Andrew, and then loaded onto trucks from the Food Bank of Central & Eastern North Carolina. Once the vegetables are bagged, they’ll make their way into 800-plus food pantries and after-school programs, boosting Jason’s message, spreading the gospel one bag of sweet potatoes at a time.

Not bad for a man who says that, some days, he still doesn’t know what he’s doing. The first lesson Jason had to learn was that he couldn’t do it by himself, and that farming, like football, is a team game. Back in the beginning, as Jason’s neighbor Len Wester planted his tobacco on the next farm over, he could see Jason up on a nearby hill. Jason was driving a tomato-red hand-me-down dinosaur of a tractor, trying to make a good run of it, kicking up dust as he swept up and down the rows. Len is a large-scale farmer, and he knew Jason’s farm better than Jason did — he’d had an arrangement with the folks who’d owned the place before. He knew of Jason’s plan to grow several acres of sweet potatoes, just to turn around and give them away. The football player’s heart was in the right place, but he had no idea what he was doing. Weakening under the noonday sun, shorthanded with aging machinery, and unprepared for attacks from swarms of mayflies, Jason bushhogged the best he could, turning in circles on the tractor till dark.

The next day, Len told Jason to meet him on the highest hill of Jason’s farm. Once there, both men looked down. Jason’s field was plowed. The sweet potato slips were packed, waiting to be planted. Len had saved Jason from himself.

“It’s a pride thing,” Jason says. Up until then, he’d been trying to learn how to farm by watching YouTube videos. He’d been afraid to ask for help because, in Jason’s words, he didn’t want to look like “a dumb jock.” And then, Len came over.

Sometimes, the Lord sends you a little help.

Labels:

first fruits farm,

jason brown

Friday, December 7, 2018

One year on: adopted girl, reunited with birth parents on a Hangzhou bridge, returns to China to teach English, learn about herself

- Kati Pohler of Michigan has returned to China and is getting to know her birth family

- Her emotional reunion with her long-lost Chinese mother, father and sister was watched by millions the world over in a BBC documentary

7047 SHARE

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Reddit

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Google Plus

- Share on Sina

MORE ON

THIS STORY

THIS STORY

At 4pm on August 26 last year, 22-year-old Catherine Su Pohler, whom everyone calls Kati, met her Chinese birth parents and older sister for the first time.

Kati’s biological mother, Qian Fenxiang, began to sob when the college student, from the American state of Michigan, arrived at the rendezvous: the Broken Bridge, in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province. Qian ran up to the young woman, whose face so closely resembles her own, flung her arms around the child she had not seen since giving her up at birth, and said repeatedly in Mandarin, “I finally get to see you. Mother is so sorry.”

That heart-rending moment caught the world’s attention. Documentary filmmaker Chang Changfu had been instrumental in bringing the two parties together, and his crew was on hand to record the scene as it unfolded on the eve of the Qixi Festival. The festival is an auspicious one for reunions: the seventh day of the seventh lunar month is the only day of the year when, in Chinese mythology, two star-crossed lovers are allowed to meet on a celestial bridge.

Chinese girl adopted in US has miraculous reunion with birth parents

Chang’s documentary aired on BBC World in December, watched by millions across the globe. This writer had interviewed Qian, her husband and Kati’s father, Xu Lida, and her adoptive parents, Ken and Ruth Pohler, for Post Magazine. The resulting feature story went viral.

Media in mainland China also gave a great deal of coverage to the meeting. It was, after all, the most universal of stories: one of love lost and found. It resonated with many of Kati’s fellow adoptees and their families, too.

The United States alone is home to more than 80,000 children who have been adopted from China since official records began, in 1999. About 85 per cent of those are female, because China’s draconian one-child policy (enforced from 1979 until 2016) meant many families – in a patriarchal society – chose to abandon or even kill baby girls so that they could try for a boy instead.

Kati reunites with her birth parents, Xu Lida (left) and Qian Fengxiang, on Hangzhou’s Broken Bridge, nearly 22 years after they gave her up. Picture: courtesy of Kati Pohler

Kati reunites with her birth parents, Xu Lida (left) and Qian Fengxiang, on Hangzhou’s Broken Bridge, nearly 22 years after they gave her up. Picture: courtesy of Kati Pohler

In many other cases, illegal second children were given up for fear of substantial fines and possible jail sentences, as was the case with Kati’s biological parents.

Reunions, experts say, are rare. Only 40 to 50 per cent of Sino-American adoptees opt to look for their birth families, according to Iris Chin Ponte, an early-education specialist, based in Massachusetts, who has spent years working with international adoptees. And she warns that the lengthy, costly and often futile searches can lead to despair.

That said, many people have been heartened by Kati’s story and have reached out to her for advice. She receives an average of three Facebook requests on the subject every day, usually from adoptees or Western couples who have adopted from China.

“It used to be a lot more. I’ve lost count of how many messages I have received,” Kati says. “I try to reply to as many as I can. They often ask if I can help them with their search in China, but there really isn’t a lot of help I can give since I didn’t look for myself.”

That, in part, is what makes her journey to Hangzhou so extraordinary.

Kati with her birth parents and older sister, Xiaochen, on the Broken Bridge as the meeting is filmed for a BBC documentary and BBC Stories. Picture: Chang Changfu

Kati with her birth parents and older sister, Xiaochen, on the Broken Bridge as the meeting is filmed for a BBC documentary and BBC Stories. Picture: Chang Changfu

China only allowed foreigners to adopt from its orphanages from 1992. The Pohlers – an evangelical Christian couple from Hudsonville, Michigan, with two biological sons of their own – visited an orphanage in Suzhou, more than 120km from Hangzhou and in neighbouring Jiangsu province, in the summer of 1996. They took home Jingzhi – the baby’s name had been included in a note written by her father, and left with her in a vegetable market.

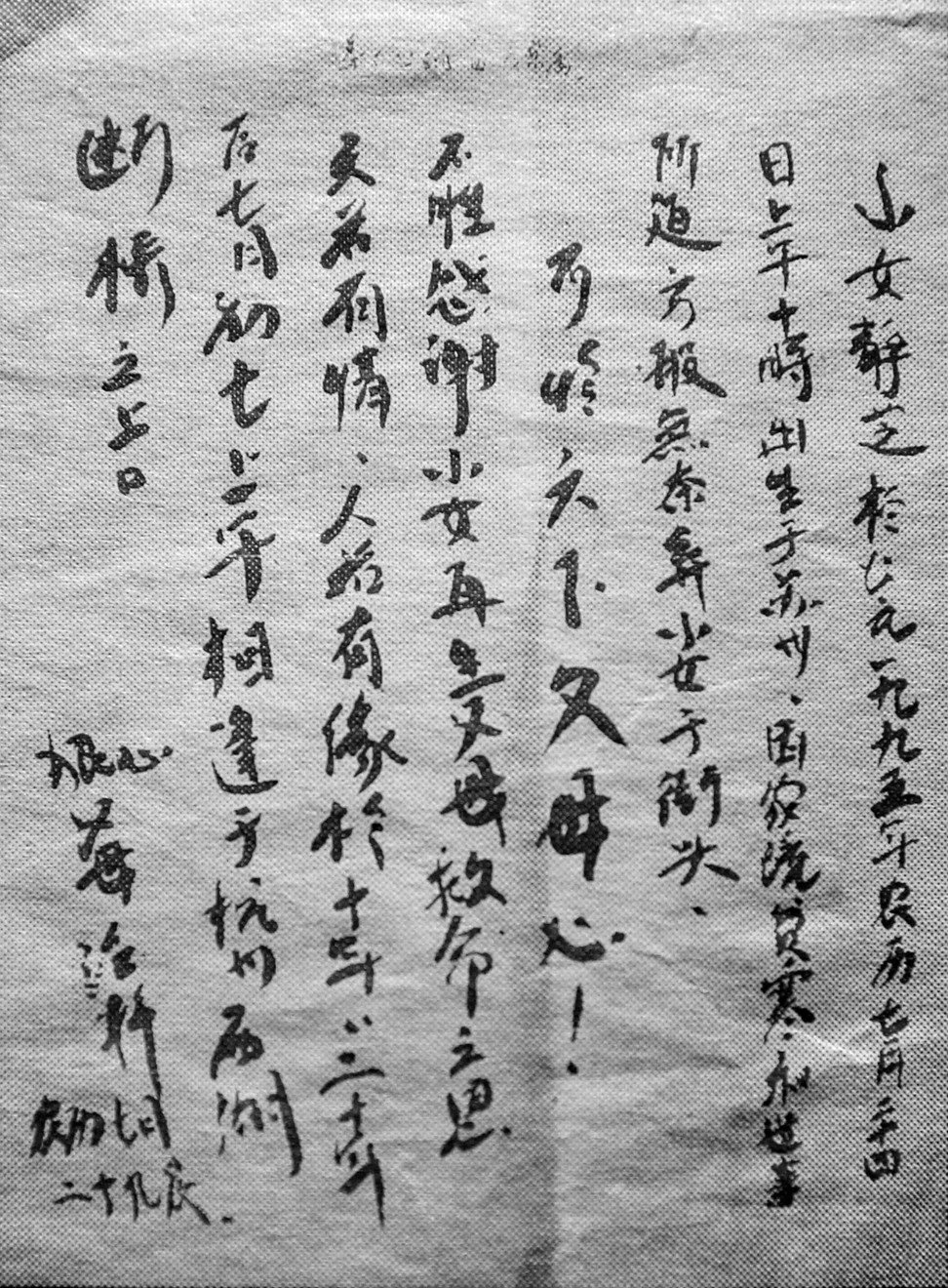

The note, written in brush and ink, read: “Our daughter, Jingzhi, was born at 10am on the 24th day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, 1995. We have been forced by poverty and affairs of the world to abandon her. Oh, pity the hearts of fathers and mothers far and near! Thank you for saving our little daughter and taking her into your care. If the heavens have feelings, if we are brought together by fate, then let us meet again on the Broken Bridge in Hangzhou on the morning of the Qixi Festival in 10 or 20 years from now.”

Kati says she never felt different from others growing up in the largely white community of Hudsonville, and had no particular desire to dig into her own background.

“I had a solid, good childhood,” she says. “Everyone knew I was adopted, obviously, so I was never asked about it.”

A copy of the note Xu Lida left with his baby daughter in 1995. Picture: Simon Song

A copy of the note Xu Lida left with his baby daughter in 1995. Picture: Simon Song

She carried on the Pohler tradition by enrolling in the religious Calvin College, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, a 30-minute drive from home, where her father and brothers had also studied. There, she worked hard and played hard – Grand Rapids is routinely voted as having one of the best craft-beer scenes in the US, and Christian students, like other young adults, are not averse to letting their hair down.

But after she turned 21, Kati made an off-the-cuff remark to her American mother about it being time she knew more about her origins. The Pohlers had known of Kati’s biological parents for some time, but had not told her for fear of disrupting her life.

Long before that, in 2005, the Pohlers had asked a friend in China to visit the Broken Bridge on the day indicated in the note delivered with Kati to the orphanage, and look for the Chinese couple. The Pohlers did not wish to provide their name or contact details – they simply wanted to tell Xu and Qian that their daughter was safe, healthy and happy.

The two parties missed each other on the bridge but later connected through a local television station, and the case was reported in the media. Intrigued by the story, Chang – a native of Jiangsu but living for many years in Pennsylvania – got in touch with Kati’s Chinese parents. He also conducted some clever sleuthing, which led him to the Pohlers in Hudsonville.

Searching for her birth parents, girl returns to China with a message

The Pohlers told Chang they would not tell Kati about her birth parents unless she were to ask about them, which the youngster eventually did, in the summer of 2016. One year later, she was standing on the Broken Bridge.

Chang’s cameras and the language barrier made an emotional first meeting even more fraught than it might have been. When, after a few days in Hangzhou, Kati said goodbye to Xu, Qian and her sister, Xiaochen, there was no guarantee they would see each other again.

Chin Ponte says it is not uncommon for there to be no attempt to build a relationship after a child has been reunited with his or her birth parents.

“In some cases, they just wanted information about their Chinese name, their real birthday and their genetic information. They call these [details] ‘truth’,” she says. “They want access to that biological information but are not interested in seeing them again or having a long-distance relationship.”

Happily for everyone in Kati’s case, however, nobody has walked away. They have been messaging regularly through Baidu’s near-perfect voice-to-text English-Chinese translator. And now, Kati, freshly graduated from college in the US, is back in China.

Kati travelling in the Czech Republic in spring. Picture: courtesy of Kati Pohler

Kati travelling in the Czech Republic in spring. Picture: courtesy of Kati Pohler

The young American arrived at the start of September, in Huaian, a city in Jiangsu some 450km north of Hangzhou, where she will teach English as a foreign language for a year. Xu and Qian drove for five hours to their second meeting but Kati was in bed with the flu, so interaction was limited.

On September 22, Kati made an eight-hour bus journey to spend the Mid-Autumn Festival weekend with her Chinese family, at their home in Hangzhou. Xu, an intense, thoughtful, chain-smoking 47-year-old, who might have been a beatnik poet in another life, was waiting in his new car with Xiaochen.

The family were anxious to ensure Kati’s visit would be perfect. Mid-Autumn Festival is the Chinese equivalent of America’s Thanksgiving, traditionally celebrated with a family feast that is finished off with mooncakes, fruit and wine, and Qian, 48, had cooked up all manner of treats. They pick me up on their way home from the bus terminal, having decided that more media intrusion might prove beneficial: a bilingual journalist could be a handy translator. Language, though, is only one of the many challenges facing them as two utterly different worlds collide.

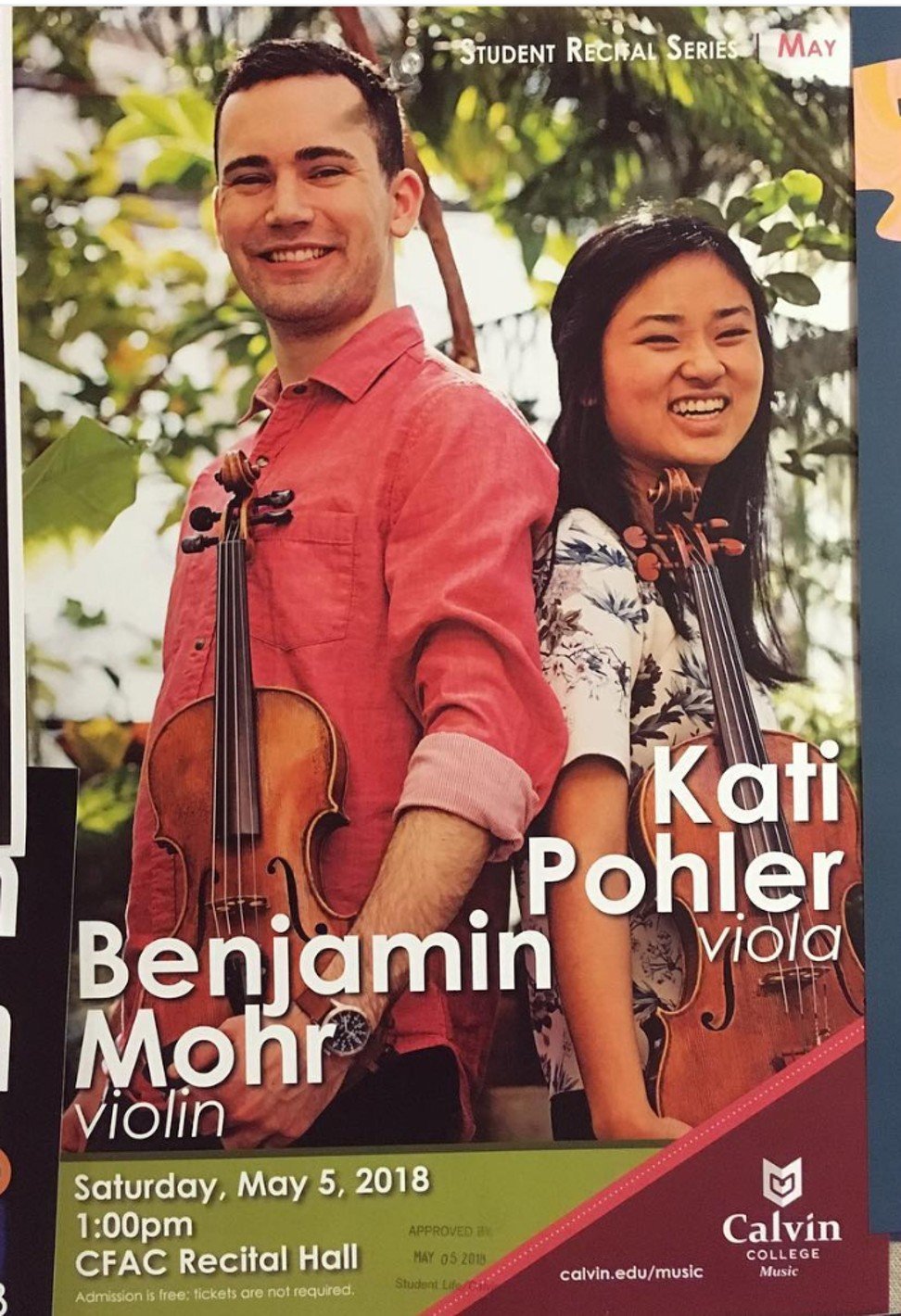

A poster for a concert Kati performed in at Calvin College, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, before she graduated this summer. Picture: courtesy of Kati Pohler

A poster for a concert Kati performed in at Calvin College, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, before she graduated this summer. Picture: courtesy of Kati Pohler

On one side, stands a fiercely independent, all-American girl who has travelled widely, plays the viola and has a boyfriend living in Scandinavia. On the other, a Chinese couple who have spent most of their lives barely subsisting. They have not travelled overseas, or even taken a holiday beyond the annual Lunar New Year break. They have lived through social and economic changes in China that outsiders can barely imagine. In less than two decades, Xu and Qian have gone from being desperately poor to living in a middle-class residential compound on the outskirts of one of China’s wealthiest cities.

We arrive at the family flat at about 8pm. Kati will spend two nights here, sharing Xiaochen’s bedroom.

There have been two major changes in the household in the past year: the parents closed their second-hand white-goods business and are taking a break for the first time in their lives; and Xiaochen has a doting boyfriend, a property agent who goes by the name Kevin, who joins us for dinner.

Qian comes out of the kitchen to give Kati a hug. She appears relaxed; a huge grin remains on her face all evening. Xu and Zhiping, his gregarious nephew, who lives nearby, make a swift run to a nearby shop, returning with a box of Yanjing beer. “I heard Kati can drink, even baijiu,” the cousin says. That Kati downed some fiery Chinese liquor when she was taken to the Xus’ ancestral village last year has entered family lore.

Soon, dishes start to pile up on the table: stir-fried vegetables and shredded meat, a tureen of turnip broth, piles of freshly steamed prawns and tiny langoustines, and the star of the show: hairy crabs – a seasonal delicacy in the eastern provinces of China.

Kati spends Mid-Autumn Festival with her birth family, at their home in Hangzhou. Picture: Simon Song

Kati spends Mid-Autumn Festival with her birth family, at their home in Hangzhou. Picture: Simon Song

Kati gamely tries everything (hairy crab and thumb-sized langoustines are challenging for a chopsticks novice). There is much good-humoured banter, and gentle teasing of Kati’s beginner-level Mandarin, which she started learning in her final year of college. The cousin tops up her glass – and his own – over and over again, with an exclaimed ganbei, or “bottoms up”.

At one point, Qian, watching Kati struggle with a langoustine, picks up an expertly shelled white nugget of flesh with her chopsticks and feeds it to the American youngster, thrilled to be exercising the parental prerogative – seemingly unchanged the world over – to embarrass one’s child.

There are video calls from relatives all evening, all hoping to catch a glimpse of Kati.

“All the extended family want to meet her, of course, but very few of them live near Hangzhou,” Xu says.

Xiaochen is two years older than Kati and the only member of the family with some English. She is kind towards the sibling she was told about as a child, but always assumed she would never meet. On the surface, the two young women are chalk and cheese. Kati is outdoorsy while Xiaochen is slight, delicate and has the pale skin of someone who avoids the sun. Xiaochen was not encouraged to work outside school because her parents slaved away for decades so that she would grow up middle class and go to university.

It has felt quite natural spending time together. We get along easily and I don’t feel I’m with a stranger

Xiaochen, Kati Pohler’s sister

Kati, while coming from an equally loving family, is from a world where the young are encouraged to be independent. She worked at a summer camp in Colorado straight after graduation, even though she was about to start a challenging teaching job in China.

Yet, they have found they are surprisingly similar in temperament. Both are softly spoken, reserved and courteous.

“It has felt quite natural spending time together,” Xiaochen says. “We get along easily and I don’t feel I’m with a stranger.”

After dinner, against the din of a typical Chinese household (musical ringtones of phones; a television variety show that nobody is watching; Qian washing up), the conversation turns more serious. Taking a deep breath, Xu asks Kati if she hates them for giving her up, and whether she had a tough time growing up without them.

“Look deep inside your heart, and tell me if you have more tolerance or hatred for us,” he says.

Kati makes several attempts to reassure them that there are no hard feelings, and that she had an enjoyable childhood. But the question keeps returning under different guises – 22 years of guilt cannot be dislodged so easily.

Kati explores Hangzhou with Xiaochen. Picture: courtesy of Kati Pohler

Kati explores Hangzhou with Xiaochen. Picture: courtesy of Kati Pohler

Cultural differences also hold a great deal of fascination, and Xu says Kati would not have come back to see them if she had grown up Chinese.

“Foreign girls and Chinese girls think differently,” he says. “A Chinese girl who was given away would never have forgiven her birth parents. It’s cultural.”

And the Chinese couple give credit to the Pohlers for allowing their daughter to come to China.

“It must have been so hard for them to let her go, especially to such a faraway country,” Qian says.

Chin Ponte has co-written a paper called “Letting Her Go”, about what a reunion between an adopted child and birth parents means for Western adoptive parents.

“It’s hard enough letting your child go to college,” Chin Ponte says. “Adoptive parents are more likely than birth parents to ask if they have done enough for the child anyway, and to ask, ‘Can we have the same emotional closeness without sharing genes? Do they love us?’”

Initially, when she found out that the Pohlers had hidden from her their knowledge of her birth parents, Kati was upset, but she has forgiven them.

Meet the American journalist who adopted abandoned Chinese babies

“There can always be more communication, but I think my parents have made a lot of progress,” she says. “They have done a good job to try and look at how I feel, without fogging things up by telling me just how it looks their way. That’s one big step forward. They have only met the Hangzhou family on a computer screen and they want to come and visit.”

Kati says she is considering further studies, either in the US or Europe, in the future. She chose China for her gap year because an American acquaintance involved in a new international school in Huaian offered her a job, and because it “makes sense” for her to be here so that she can learn more about herself and her family.

As at many family dinners the world over, the group stays clear of two topics: religion and politics. The Chinese are aware of Kati’s Christian faith, but do not consider that to be any more odd than other Western habits. And the American president’s name is not mentioned once, despite the raging US-China trade war.

More important is the subject of boyfriends, and Kati mentions that she plans to spend the 2019 Lunar New Year holiday in Denmark, where her sweetheart is a graduate student. “Bring him here instead,” Qian and Xu say in chorus, offering to take the pair “to many different places”.

I call Xiaochen ‘sister’ in Mandarin, because I don’t have a sister in America. But I do not call my birth parents mother and father, because I have a mother and father at home

Kati Pohler

The warmth the group shares is infectious, but Kati knows there are still issues to work through. How, for instance, should she address Xu and Qian?

“I call Xiaochen ‘sister’ in Mandarin, because I don’t have a sister in America,” she says. “But I do not call my birth parents mother and father, because I have a mother and father at home. I don’t call them anything at the moment.”

The Chinese couple, however, are unequivocal when it comes to calling Kati their daughter.

“I left the note because I hoped we would see her again,” Xu says. “We didn’t mean to abandon her forever.”

As Qian brings out the mooncakes and fruit, she asks Kati if she knows how long she will stay in China. Kati gives a vague answer, and observes that parents everywhere are alike. “They never want to say goodbye,” she says.

“Of course, your parents would worry when you come so far on your own,” Qian says.

“But I don’t like people worrying about me,” Kati protests. And that, of course, is the prompt for a universal truth that parents of all races, creeds and colours acknowledge..

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)