GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. -- It was a simple letter, with a simple request.

"Is it possible that in 10 years that you could meet us on this bridge?"

The request to meet came from two Chinese parents who had abandoned their second-born child in a Chinese market. They had violated China's one-child policy, and their child -- Kati -- was adopted by Ken and Ruth Pohler.

"It was so heartfelt. And we thought, 'Oh my, these birth parents went through a difficult time," Ken remembered.

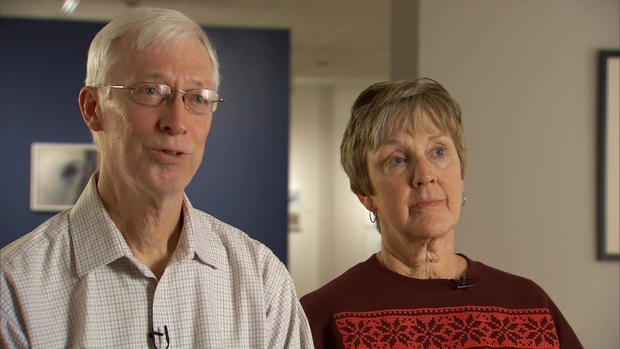

Ken and Ruth Pohler

CBS NEWS

The Pohlers never forgot that note with Kati's Chinese name. When she turned 10 in 2005, they sent a messenger to the bridge. Kati's birth father was there, and by chance, a Chinese TV crew captured him on tape.

"Holding a sign. The name on the sign was the name in the note," said Changfu Chang, a filmmaker.

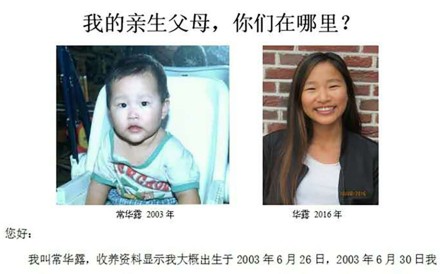

As a child, Kati Pohler said she wanted to know where she came from

CBS NEWS

He was so compelled by the story, he made a documentary about it. The story became famous in China, but back in the U.S., the Pohlers remained silent.

"When I was little, I would ask my mom like, whose tummy did I come from," said Kati Pohler. "I realized that I didn't come from her tummy."

But the Pohlers didn't tell Kati until she was 20.

"They told my brothers about it. So I was the only one left in the dark," she said.

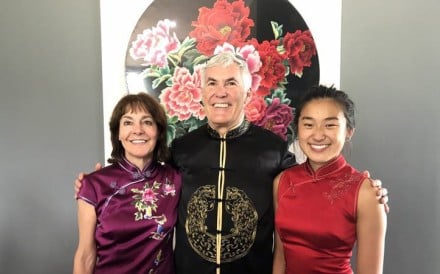

Kati Pohler got to meet her birth parents in China at 22

CBS NEWS

She admits that made her upset, but this summer, Kati finally got a chance to meet her birth parents a week after her 22nd birthday when she traveled to China. It was a reunion made all the more overwhelming by the barriers of both language and culture.

"They are very real to me now," said Kati.

© 2018 CBS Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved.

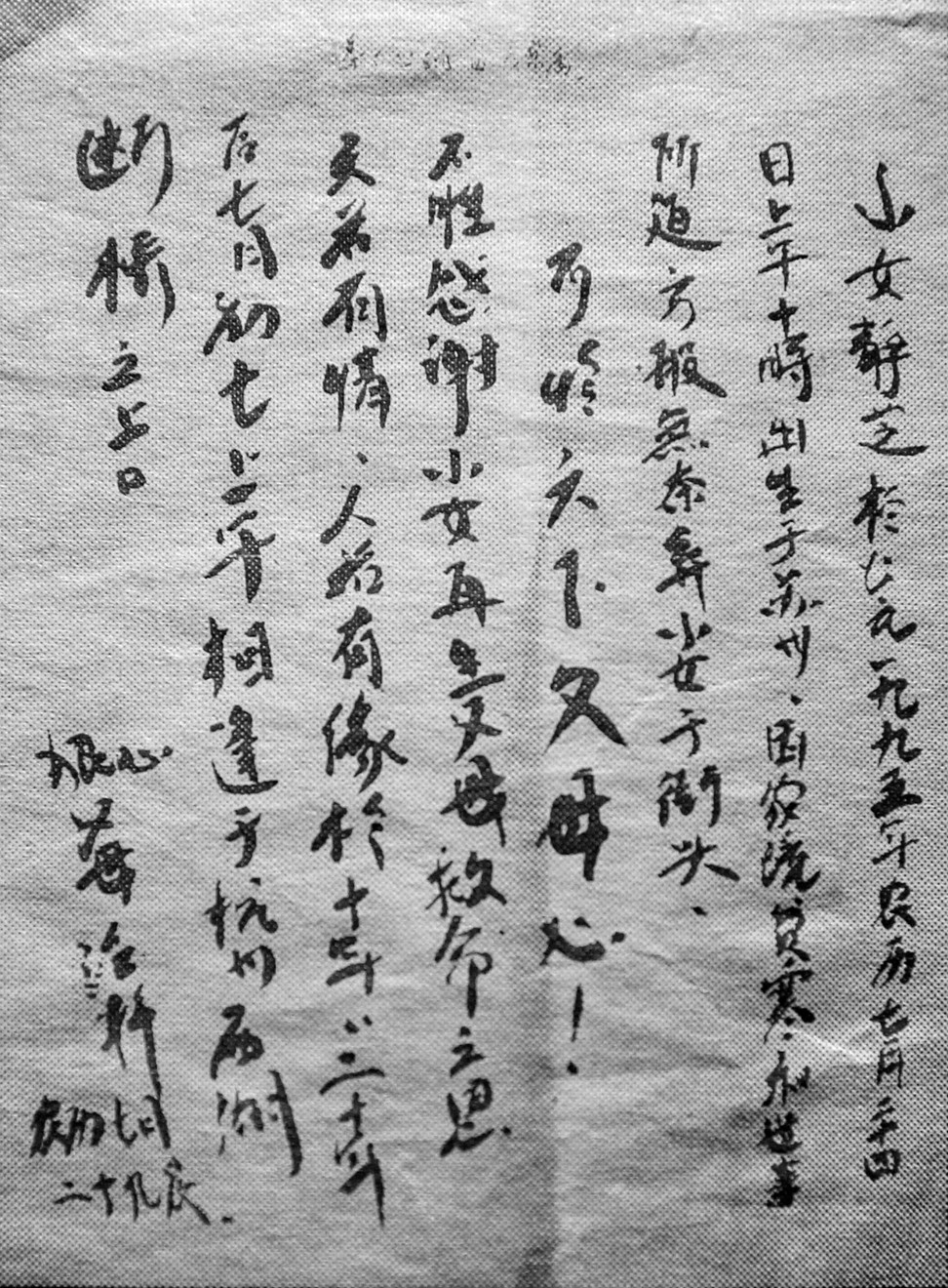

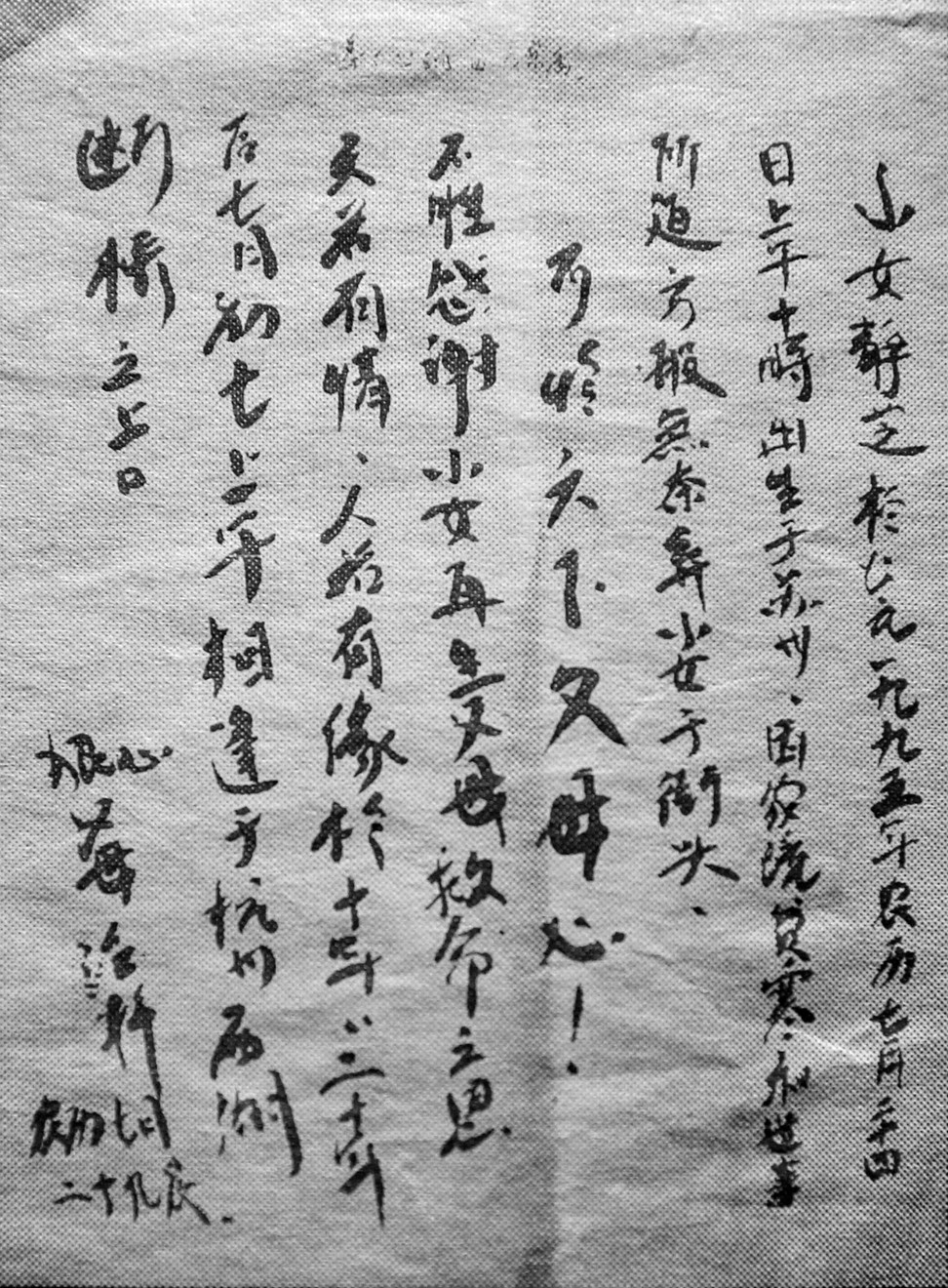

A copy of the letter Xu left with his daughter. Picture: Simon Song

A copy of the letter Xu left with his daughter. Picture: Simon Song

Kati is reunited with her birth parents and older sister, Xiaochen, on the Broken Bridge as the meeting is filmed for a BBC documentary and BBC Stories. Picture: Chang Changfu

Kati is reunited with her birth parents and older sister, Xiaochen, on the Broken Bridge as the meeting is filmed for a BBC documentary and BBC Stories. Picture: Chang Changfu

Xu and Qian are reunited with their US-raised daughter, Kati, on the bridge, nearly 22 years after they gave her up.

Xu and Qian are reunited with their US-raised daughter, Kati, on the bridge, nearly 22 years after they gave her up.

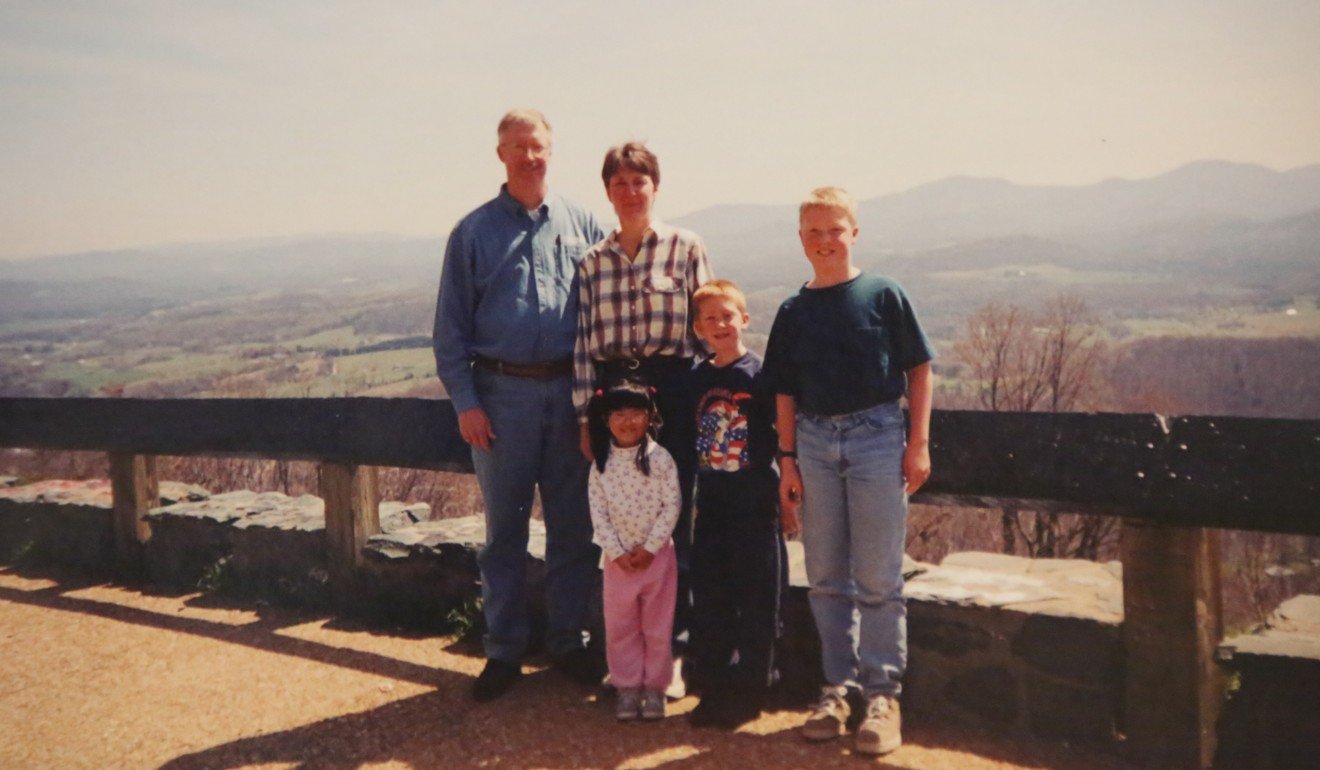

Kati with her adoptive parents, Ken and Ruth, and brothers, Steven (right) and Jeff, in the US.

Kati with her adoptive parents, Ken and Ruth, and brothers, Steven (right) and Jeff, in the US.

Kati with Ruth and Jeff.

Kati with Ruth and Jeff.

Xu and Qian on their wedding day circa 1991.

Xu and Qian on their wedding day circa 1991.

Xu and Qian in their electrical appliances shop. Picture: Simon Song

Xu and Qian in their electrical appliances shop. Picture: Simon Song

Xu holds up a newspaper article dated August 17, 2005, about the couple’s search for their daughter. Picture: Simon Song

Xu holds up a newspaper article dated August 17, 2005, about the couple’s search for their daughter. Picture: Simon Song

Xu and Qian at home in Hangzhou. Picture: Simon Song

Xu and Qian at home in Hangzhou. Picture: Simon Song

Xu shows a picture of Kati on his mobile phone, on the Broken Bridge. Picture: Simon Song

Xu shows a picture of Kati on his mobile phone, on the Broken Bridge. Picture: Simon Song

Qian, Kati, Xu and Xiaochen on the Broken Bridge.

Qian, Kati, Xu and Xiaochen on the Broken Bridge.

Kati, in Baltimore, in the United States, in January 2017.

Kati, in Baltimore, in the United States, in January 2017.

Chinese girl adopted by American family miraculously reunited with her birth parents on Hangzhou’s Broken Bridge

‘Let us meet again on the Broken Bridge in Hangzhou on the morning of the Qixi Festival in 10 or 20 years’, read the note her parents left with the baby who would grow up as Kati Pohler in Michigan. Thanks to a lucky encounter, eventually they did

/ UPDATED ON

MORE ON

THIS STORY

THIS STORY

Twenty-two years ago, a heavily pregnant Qian Fenxiang hid herself and her three-year-old daughter on a houseboat on a secluded Suzhou canal, 120km away from her home in Hangzhou, and waited.

Six weeks later, she gave birth on the boat to a second daughter, a child who should have been aborted under China’s draconian one-child policy, introduced in 1979 as a means to reduce poverty.

Xu Lida, her husband, had cut the cord with a pair of scissors he had sterilised with boiling water and, for a do-it-yourself delivery, all seemed to be going well – until the placenta wouldn’t drop. It was a dangerous complication, but hospital care was out of the question. Fortunately for the couple, there was a small clinic near where they were moored, and a doctor who agreed to help without alerting the authorities.

Five days later, the then 24-year-old Xu got up at dawn and took the baby to a covered vegetable market in Suzhou. There, he left the girl with a note written in brush and ink: “Our daughter, Jingzhi, was born at 10am on the 24th day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, 1995. We have been forced by poverty and affairs of the world to abandon her. Oh, pity the hearts of fathers and mothers far and near! Thank you for saving our little daughter and taking her into your care. If the heavens have feelings, if we are brought together by fate, then let us meet again on the Broken Bridge in Hangzhou on the morning of the Qixi Festival in 10 or 20 years from now.”

A copy of the letter Xu left with his daughter. Picture: Simon Song

A copy of the letter Xu left with his daughter. Picture: Simon Song

Dubbed Chinese Valentine’s Day, the Qixi Festival falls on the seventh day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar and marks the day when the mythical cowherd and his lover, the weaving maiden, are allowed to see each other on a bridge formed by magpies in flight.

‘It’s like having your insides ripped out’: Singaporean air crash widow

The Broken Bridge – which is not actually broken – is no less evocative. The short span between the shore of Hangzhou’s West Lake and the scenic Bai Causeway was mentioned in an eighth-century Tang dynasty poem. In the traditional story White Snake, it is here that the White Lady and her lover, Xu Xian, first meet.

It wasn’t exactly 10 or 20 years later, but on the eve of the Qixi Festival this year, Qian and Xu finally laid eyes on Jingzhi – their healthy, intelligent college student daughter who is known as Catherine Su Pohler by her American adoptive parents.

Kati is reunited with her birth parents and older sister, Xiaochen, on the Broken Bridge as the meeting is filmed for a BBC documentary and BBC Stories. Picture: Chang Changfu

Kati is reunited with her birth parents and older sister, Xiaochen, on the Broken Bridge as the meeting is filmed for a BBC documentary and BBC Stories. Picture: Chang Changfu

That first sighting was the stuff of reality television. Indeed, a television crew was on hand at the Broken Bridge to capture the scene as Qian and Xu ran to Kati, as she is called by everyone who knows her. The story of how they were reunited is the subject of a BBC documentary that will air this week.

Three months after the meeting, however, it is unclear whether this story of improbable coincidences will have a fairy-tale ending.

“We still feel so much guilt. If we hadn’t abandoned her, she wouldn’t have to suffer so,” says an emotional Qian, when Post Magazine visits the couple at their home in Hangzhou. She is using the Mandarin term chiku, to describe Kati’s life in America. It literally means “eating bitterness”.

Considering the bitterness that the couple have swallowed over the years, it is surprising to find that the stout, kind-looking Qian doesn’t feel more relieved that Kati has grown up in a comfortably middle-class suburban American home.

Xu and Qian are reunited with their US-raised daughter, Kati, on the bridge, nearly 22 years after they gave her up.

Xu and Qian are reunited with their US-raised daughter, Kati, on the bridge, nearly 22 years after they gave her up.

Baby Jingzhi and the note were delivered to Suzhou city’s children’s welfare institute. Around the same time, Ken and Ruth Pohler of Hudsonville, Michigan, decided to adopt.

“We didn’t really think it mattered which country we adopted from but we have a brother-in-law who is Chinese and Ruth’s sister adopted from China, too, which was neat,” says Ken, from the house where Kati grew up, about 30km from Lake Michigan. He and his wife are evangelical Christians with two boys of their own, but they wanted a third child.

Adopted from China, raised in the USA: images of Chinese children and their new American families

In the summer of 1996, 10 American couples were taken by Bethany Christian Services, one of the biggest international adoption agencies for Americans, to the Suzhou orphanage. There, they picked up their new daughters – they were all daughters because of the traditional Chinese preference for sons. As they boarded the tour bus with Jingzhi, the Pohlers showed a translator the note that had come from the baby’s birth parents.

“She was so moved by it, she was in tears while she read it out to us. It was such a heartfelt message,” Ken says. But the couple had no intention of telling Kati about it until she was at least 18, and only then if she showed interest in finding out about her past life.

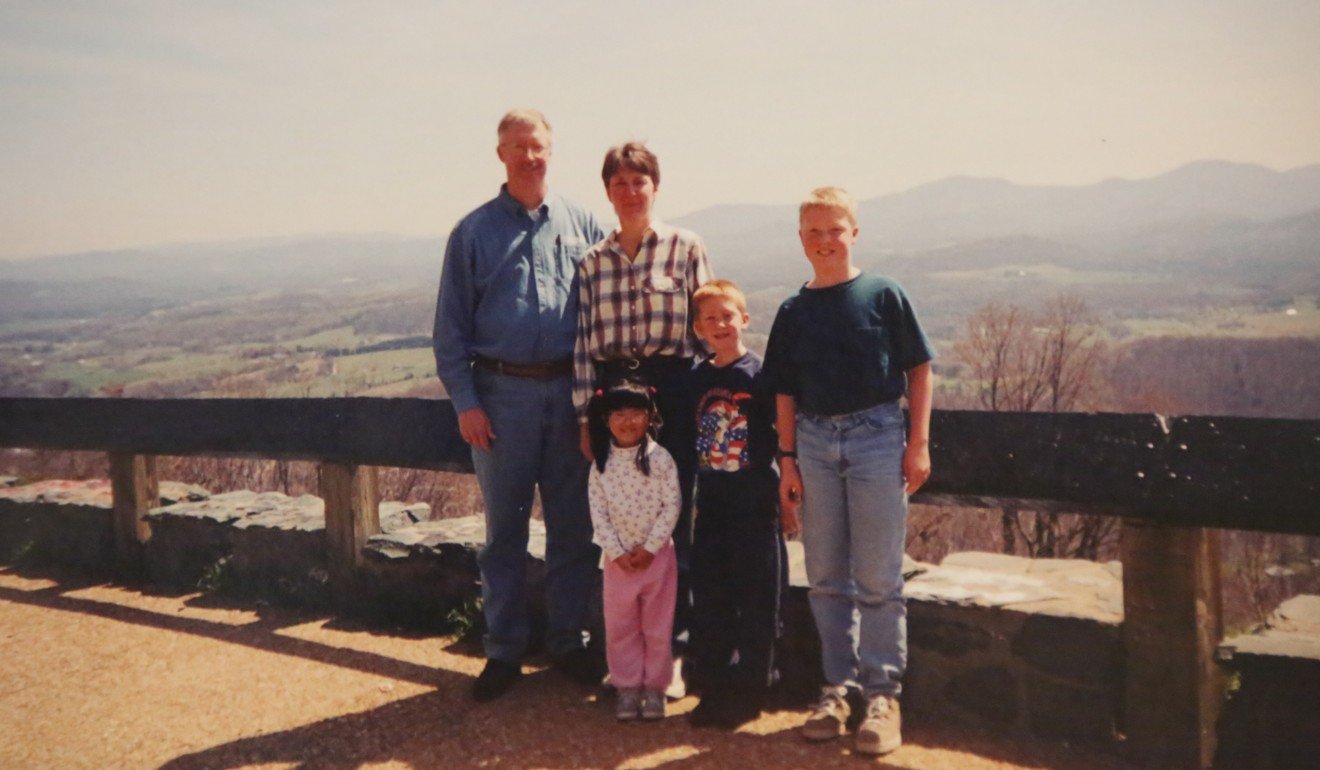

Kati with her adoptive parents, Ken and Ruth, and brothers, Steven (right) and Jeff, in the US.

Kati with her adoptive parents, Ken and Ruth, and brothers, Steven (right) and Jeff, in the US.

Kati was brought up as most of the other children were in the town of about 7,000 people. Close-knit Hudsonville is predominantly Caucasian, as is Calvin College, the liberal arts university affiliated with the Christian Reformed Church where Ken is a campus safety supervisor and where Kati is now studying public health and music.

“I had a solid, good childhood,” Kati says. “Everyone knew I was adopted, obviously, so I was never asked about it.”

YouTube clip helps woman adopted in Fanling in 1960s find birth mother

She describes her family as “very religious” and close.

“My two brothers are quite a bit older. I guess if I felt different, it was because I was the youngest and I was a girl,” she says.

The family albums are filled with photographs of young Kati winning sports tournaments, practising the viola and piano, travelling across America on family and school trips, and generally looking healthy and outdoorsy, wearing a smile that shows off her perfect American teeth.

Kati with Ruth and Jeff.

Kati with Ruth and Jeff.

However, like many college students in America, she works the odd shift to earn extra cash, in Kati’s case, in a greenhouse. To Qian, that is awful.

“My Xiaochen [her first daughter] here has never had to wash a single bowl,” she says.

Qian finds it unbelievable that working part time can be part of growing up in a wealthy country like America.

Equally, Qian and Xu’s experience as migrant workers would seem unbelievably hard to an average American, as would the enormous sacrifices that millions like them have made during their country’s march towards prosperity.

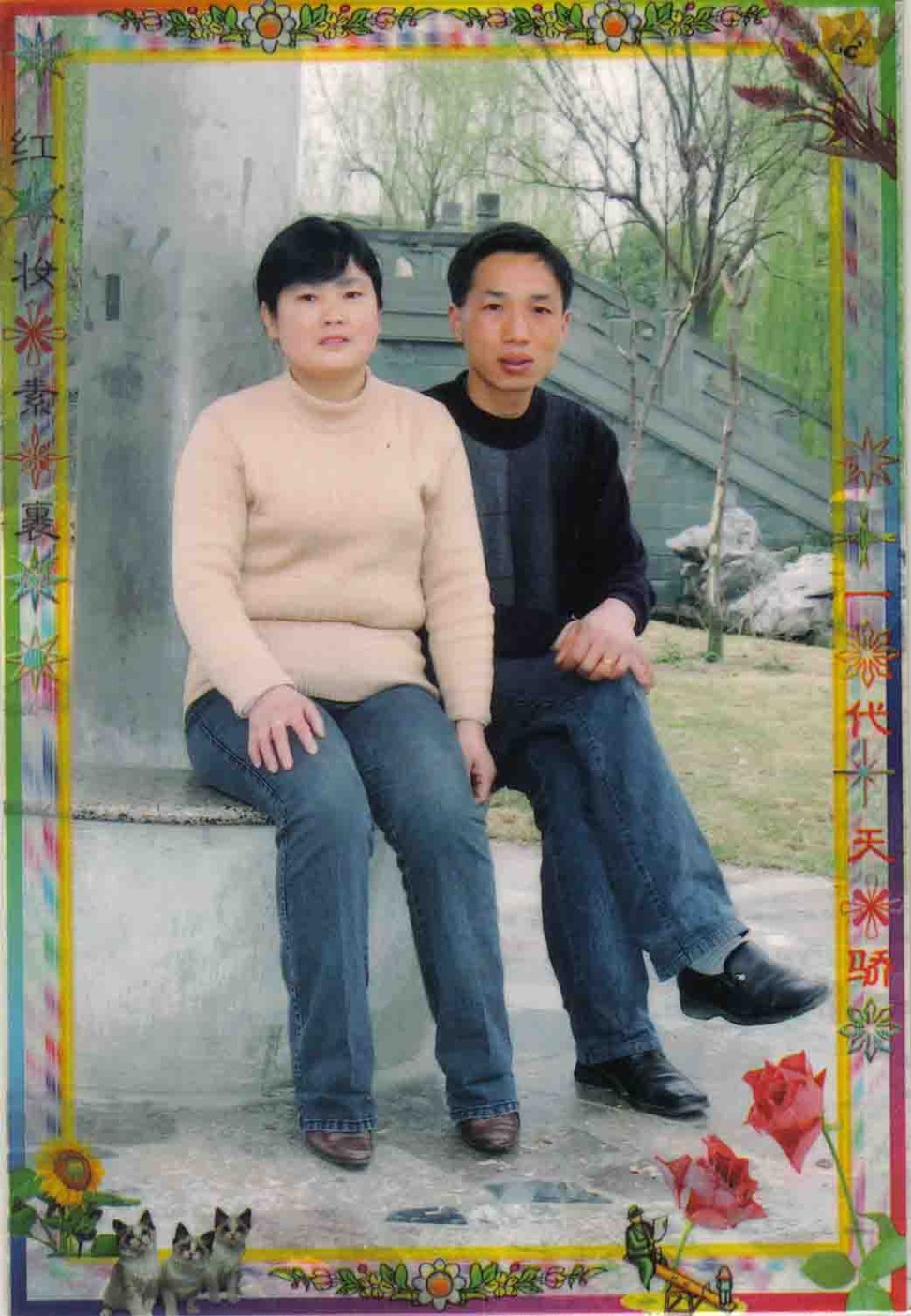

Qian and Xu grew up in Baoying county, near Yangzhou in Jiangsu province – birthplace of the world’s most famous rice dish. Xu, wiry, weather-beaten, with an irrepressible good humour, was born in 1971. He finished junior high school and moved in 1987 to Hangzhou, a five-hour drive away. He was joining millions of others who turned their backs on their ancestors’ farms to seek better-paid work in China’s fast-growing cities.

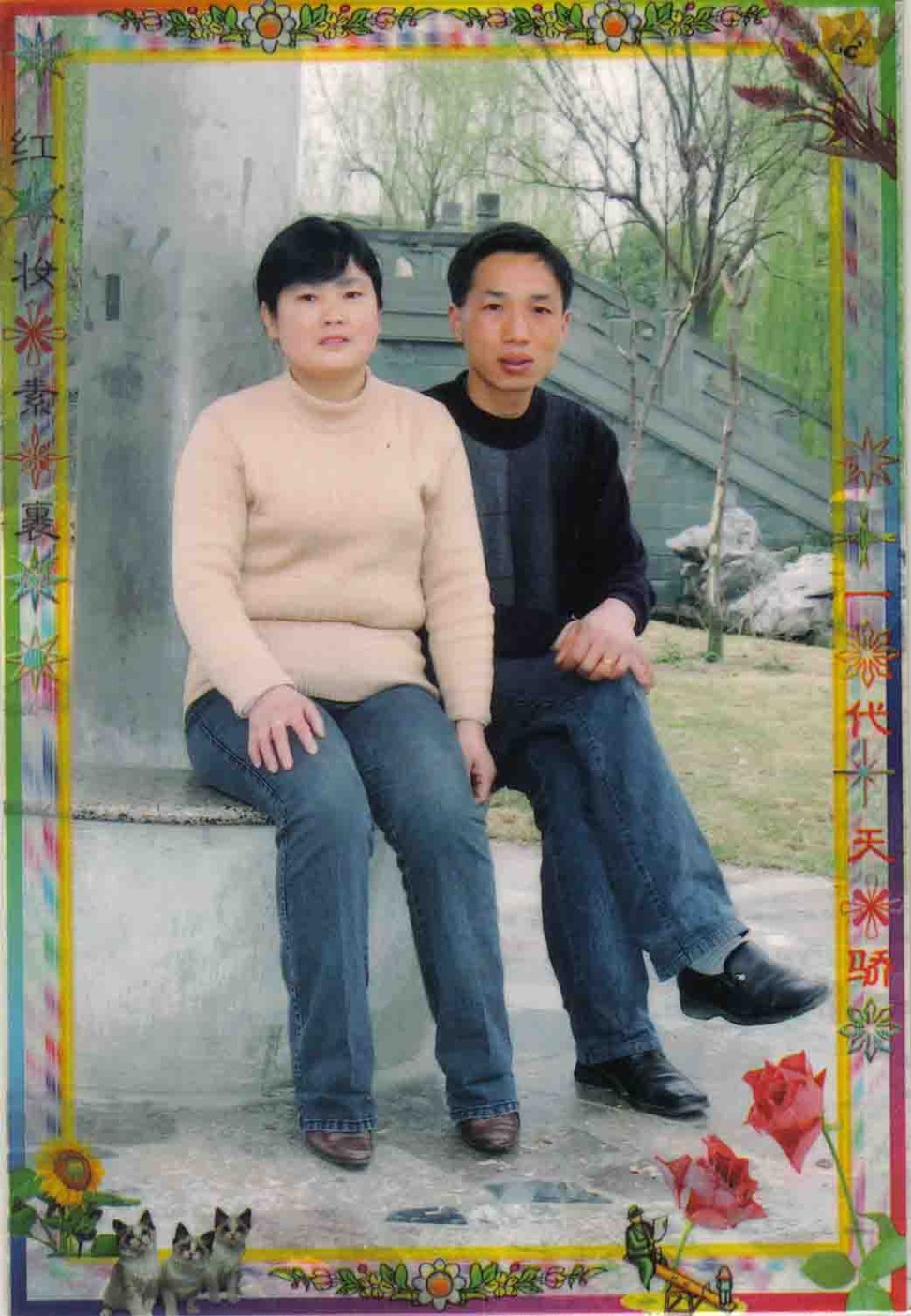

Xu and Qian on their wedding day circa 1991.

Xu and Qian on their wedding day circa 1991.

The only work the 16-year-old could find was collecting household scraps. But he worked hard and saved enough money to return home a few years later and marry Qian, a fellow villager. The two set up home in a rented room in one of many rudimentary cottages on the outskirts of Hangzhou housing migrant workers. They were so far removed from public services that when Qian went into labour with Xiaochen, Xu had to put her in the back of a delivery tricycle and pedal for miles to the hospital.

Still, the couple made the best of things and dreamed of having a better life some day. It was a good time to be in the scrap trade-in one of China’s wealthiest cities; national gross domestic product in the years before the 1997 Asian financial crisis was growing at a staggering 13 per cent.

With their optimism came the idea of giving Xiaochen a sibling.

“We thought we could get away with it since we lived so far away from the family planning cadres in our village,” Xu says. “We thought the sheer size of the city would give us cover.”

But they soon learned just how brutal the regime could be. The one-child policy led to more than 300 million abortions, many of which were forced, an unknown number of female infanticides, a terrifyingly efficient spying system and the heavy fines and extortion that served as punishment for those who exceeded their quota.

‘I could hear the baby cry. They killed my baby … yet I couldn’t do a thing’: The countless tragedies of China’s one-child policy

The decision to give up Jingzhi had nothing to do with the fact that she was a girl, her birth parents say. In fact, they wouldn’t have known her gender when they decided that, given the horror stories they had heard, they wouldn’t be able to keep the baby. By then, Qian was five or six months pregnant and it was too late for an abortion.

The couple now own a business selling second-hand white goods as well as a comfortable, two-bedroom flat. But theirs is still a hard life. Xiaochenhas a full-time job but her parents still start work every day at 7am and never take a day off, except over Lunar New Year. They have never even been to Yangzhou, let alone outside Jiangsu province.

Xu and Qian in their electrical appliances shop. Picture: Simon Song

Xu and Qian in their electrical appliances shop. Picture: Simon Song

Qian runs the shop – a sectioned-off area in a vast, open-air electrical appliances wholesale market that is bitterly cold in the winter. She waits for business as she shuffles between rows of washing machines, flat-screen televisions and refrigerators her husband has acquired and upcycled. It all came as a bit of a shock for the humble couple to find themselves on national television in 2005.

Kati turned 10 in 2005, and Qian and Xu went to the Broken Bridge on the Qixi Festival, as planned.

“We got there early, and we carried a big sign with our daughter’s name and words similar to those we used in the original note. We felt like running up to every girl we saw on the bridge,” Xu says. “It was awful.”

Nobody met them, and they left just before 4pm, hungry, thirsty and drained by disappointment.

China’s one-child policy has a legacy of bereaved parents facing humiliation and despair

The Pohlers, meanwhile, had asked a friend of a friend to visit the bridge that day.

“We remembered the 10th-year promise in the note,” Ken says. “We prayed about it and talked to a friend who often travelled to China for business. He said he could ask a friend called Annie Wu to try and find the birth parents on the bridge. We didn’t want to involve Kati in something as vague as this. But it was important to us that the birth parents knew their daughter was adopted by a family who love her very much and provide her with a good home.”

Wu arrived at the bridge just after 4pm, missing Qian and Xu by minutes. Having checked there were no distressed parents to be seen, she was getting ready to leave when she noticed a television crew filming on the bridge. She asked if they could check their footage to see if anyone who looked like Kati’s birth parents had been there. By sheer luck, Xu had been caught on camera, holding up his sign showing the name Jingzhi clearly.

This was television gold. The station immediately broadcast the story, which the national CCTV network and newspapers picked up.

Xu holds up a newspaper article dated August 17, 2005, about the couple’s search for their daughter. Picture: Simon Song

Xu holds up a newspaper article dated August 17, 2005, about the couple’s search for their daughter. Picture: Simon Song

A friend in Hangzhou saw one of the TV reports and told the birth parents there was news of Jingzhi. The elated couple met Wu through the TV station, and were handed a typed letter from the Pohlers (their names withheld) and some photographs. They were assured there would be further news.

Unfortunately for Qian and Xu, it was to be a long time before they saw their lost daughter in the flesh. Once they were told of developments, the Pohlers asked Wu to cease contact with Qian and Xu immediately.

“We took what we could from Annie, and saw no more need for contact,” Ruth says. “We thought that we should wait for Kati to grow and see if she wanted more information. She’s our daughter. Yes, she has her birth parents but a deeper relationship with them would really complicate matters.”

Wu changed her phone number and couldn’t be reached by Qian and Xu or the media again.

End of China’s one-child policy sees births rise to 18.46 million in 2016 … but it’s still not enough

The couple had no doubt Kati was their Jingzhi. She has her mother’s eyes. Just as an astronomer might scan the skies ceaselessly in search of a signal he picked up once from another galaxy, the couple returned to the Broken Bridge every Qixi Festival.

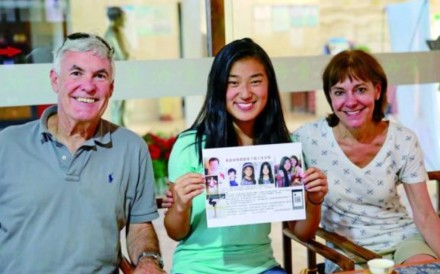

This is where documentary maker Chang Changfu enters the picture.

“I had made a film about international adoptees from China before and a friend told me about this couple who went to the Broken Bridge to find their daughter,” the Chinese-American says. “It’s an irresistible story.”

Xu and Qian at home in Hangzhou. Picture: Simon Song

Xu and Qian at home in Hangzhou. Picture: Simon Song

Chang met Qian and Xu and decided to try to track down the American parents using the little evidence he had: the typed letter from the Pohlers mentioned that Kati had been adopted in Suzhou, that she had rheumatoid arthritis at a young age and that they lived in Michigan.

The internet gods must have been smiling on him, for he chanced upon an online message board on which American parents who had adopted from Suzhou’s only orphanage shared their experiences. One message was from a Ken Pohler, who mentioned his daughter had a knee problem as a youngster. Chang found a photograph of Pohler online that matched the image of the man in one of the pictures Qian and Xu had been given.

Chang made contact but it took him a few years to convince the Pohlers he had no ulterior motive other than to help with any further communication. The Pohlers explained to him why they had resisted stirring up the past, and why they would not make contact with the birth parents the year Kati turned 20.

Xu shows a picture of Kati on his mobile phone, on the Broken Bridge. Picture: Simon Song

Xu shows a picture of Kati on his mobile phone, on the Broken Bridge. Picture: Simon Song

Last year, when Kati was 21, she was preparing for a semester as an exchange student in Spain when, she says, “I thought people there would have questions about me being Chinese and American. So I asked my mother to tell me about my past again, and she said, ‘Well, we should tell you that we actually know who your biological parents are.’ I was so shocked.”

Kati knew immediately that she wanted to meet them, but she was also terrified by the prospect, and it took time for her to get over the anger she felt towards her adoptive parents. She felt betrayed for having been kept in the dark.

She got in touch with Chang after telling the Pohlers of her intentions, and agreed to become the subject of a documentary about her search for her birth parents. The filmmaker had the heart-warming climax already planned: Qixi Festival 2017; Kati surprising her birth parents on the Broken Bridge. Kati and Chang would meet a few days earlier in Suzhou, to film in the vegetable market where she was abandoned.

Chinese teenager reunited with family 16 years after being snatched from his home

Withholding this information from Qian and Xu would have been less cruel had the filming had gone according to plan. Unfortunately, Wu – back in the picture after Kati decided to visit China – had tipped off the birth parents. Qian and Xu took themselves to Suzhou to find Kati, only to be told that, for the sake of dramatic effect, the first meeting had to take place on the Broken Bridge. Deeply hurt, the couple had, in fact, been turned away because Kati was feeling overwhelmed by the experience, she tells me.

When they finally met on the bridge, Qian broke down and sobbed uncontrollably as the many years of yearning cracked open her battle-hardened shell. This was her daughter’s homecoming.

Kati stayed in her birth parents’ flat for two days and shared a room with her sister, who speaks only limited English.

Qian, Kati, Xu and Xiaochen on the Broken Bridge.

Qian, Kati, Xu and Xiaochen on the Broken Bridge.

“It was really nice to see them. I was surprised by how emotional my Chinese mom was,” she says.

Kati was bemused too by the typical Chinese admonition that she received. “The first thing they said was, ‘You are skinny, you’ve got to eat more.’ If I didn’t eat they would feed me. I guess they were just super-excited and missed looking after me for all these years,” she says.

The couple took her back to their hometown, and there, Kati met Xu’s ailing mother. She hasn’t spoken since she had a stroke several years ago but she let her lost granddaughter hold her hand. Kati’s grandmother had been there on the houseboat all those years ago to help with the delivery.

Chinese sisters, abducted as teens, reunited with mother after 28 years

Kati admits she hasn’t begun to process the experience.

“I want some sort of relationship. I want to see them again. But the big question is, what are they to me? I don’t even know what to call them,” she says.

Before her trip, the Asian side of her was purely physical. “Now, it’s deeper than that. It’s good that I am more in touch with where I came from, but it is also confusing. I am a product of where I grew up and that is not Asian in any sense of the word,” she says.

Kati, in Baltimore, in the United States, in January 2017.

Kati, in Baltimore, in the United States, in January 2017.

For Qian and Xu, seeing Kati doing well was a huge relief and helped to ease the remorse they have been carrying for more than 20 years. But the reunion has also left them hungering for more – and it seems unlikely they will get what they want.

“We were disappointed that she wouldn’t call us mama and baba. We asked her to, but she said they didn’t do that in America, that they called their parents by their first names. Is that right?” Xu asks.

“We couldn’t communicate meaningfully since we don’t speak English and she doesn’t speak Mandarin, but we could tell she’s a really nice girl. But now that we have met her, we miss her even more than before,” Qian says.

“I guess we can only tell ourselves she is like a daughter who has been married off.”